- Home

- Sue Townsend

Adrian Mole: The Cappuccino Years Page 18

Adrian Mole: The Cappuccino Years Read online

Page 18

Sunday November 23rd

To The Lawns to set fire to William’s Christmas list in their open fireplace. This method of sending the list to Santa is a Mole tradition that I am determined to keep up. I won’t easily forgive my parents for boarding up our own fireplace and putting a storage heater in the gap between the plywood and the fender.

William wants:

1. Po

2. Tinky Winky

3. Laa-Laa

4. Dipsy

5. And the other one whose name always escapes me.

My father said, ‘You do realize, don’t you, that there’s none to be had?’ He pronounced the aitch in ‘had’. He pronounced ‘that’ as thet. He was wearing Timberland deck-shoes, and stroking Henry’s glossy head. He is Eliza Doolittle to Tania’s Henry Higgins.

Monday November 24th

Took the New Dog to the vet’s to get its nails cut. It keeps skidding across the kitchen lino like Torville or Dean, whichever is the hairiest.

An envelope containing my fan mail came today. A man in Wolverhampton, Edwin Log, wrote to tell me that he has eaten offal every day of his life for forty-five years and ‘enjoys perfect health’. A woman in Battersea said I was encouraging the ‘mass murder of the innocents’. She said she would like to see me hung by my intestines from Blackfriars Bridge.

Tuesday November 25th

William asked me why I don’t go to work ‘like other daddies do’.

I told him that I am a published author and a TV presenter – a personality in fact. I pointed to the five fan letters on my desk/dressing-table and said, ‘People out there love me.’

William went to the window and looked down on the street. ‘There’s nobody out there,’ he said.

Thursday November 27th

3.30 a.m. I am at William’s hospital bedside. He is being kept in overnight for observation after placing a coffee bean in his left ear ‘to see if it would rattle’.

It has been removed, but they had to give him a general anaesthetic. It has been the most harrowing night of my life, it took me, my mother and two nurses to hold him down while a tiny woman doctor, called Surinder, examined his ear with an illuminated probe. The casualty department at the Leicester Royal Infirmary was rent with his screams. When the decision was made to operate I turned on my mother in my anguish saying, ‘I hold Ivan Braithwaite responsible. It was he who introduced the coffee bean to Wisteria Walk.’

She didn’t respond in the way I expected. Instead she said, ‘I hear what you’re saying, I hear your anger.’

I was in the recovery room with William when he came round from the operation. He cried for my mother. A nurse saw that I was upset by this and said, ‘He doesn’t know what he’s saying.’ But I think he did know. I now realize that I’m not the most important person in his life, as he is in mine.

Friday November 28th

William is a lovely boy – especially when slightly sedated by prescription drugs. I am writing this in the hospital restaurant – Nightingales. I am alone in the seventy-seat non-smoking section. Whereas the small smoking section is crammed full of doctors and nurses. Why don’t they see the light and give up? Had an All-Day Breakfast, was annoyed when they forgot my black pudding. Went to counter to complain, was told it was either mushrooms or black pudding. I offered to pay extra for the black pudding, but was told the computerized till wouldn’t allow this. Raised voice to fat girl with pretty face behind counter.

She said, ‘It’s not my fault.’

I said, ‘Nobody accepts responsibility for anything any more. Nobody apologizes, nobody resigns.’

She looked mystified.

Went back to non-smoking section to find smokers goggling and All-Day Breakfast congealed on the plate.

3 p.m. Still here, at bedside. Nurses in love with William. He has told them that he is having all four Teletubbies for Christmas. A very nice staff nurse called Lucy came up to me and said, ‘If you’ve got a source, I’m desperate for a Po.’

I confessed that I had no Teletubby ‘insider knowledge’. This is quite worrying: perhaps I should start a search.

I asked why William had not been discharged yet. Staff Nurse Lucy (blonde, slim, fair hairy arms, breasts 5/10) said, ‘Dr Fong is slightly concerned about the bruising on his lower back.’ I explained that William had fallen off the arm of the sofa while pretending to take a corner as Jeremy Clarkson. Lucy, who has a three-year-old daughter, said, ‘They’re mad at that age, aren’t they?’ and laughed. However, Dr Fong had never heard of Jeremy Clarkson, and obviously didn’t believe my explanation.

Saturday November 29th

Royal Infirmary– Nightingales

Still here. William’s body and mind are under investigation. I have pleaded with him to stop saying, ‘No, Dad, no,’ etc., but he has turned into a fiend. I left him surrounded by his adoring grandparents and step-grandparents, who are showering him with toys and sweets and pop-up books. No wonder he doesn’t want to come out.

Lucy is a single parent like me. Her daughter is called Lucinda. Staff Nurse Lucy said that Lucinda can also be a fiend, and once shouted, ‘Are you going to lock me in the cupboard when we get home, Mummy?’ in the queue at Homebase. Lucy’s relationship with a policeman has just broken up because of his deception when on a late shift. She said, ‘I really enjoy talking to you, Mr Mole, or can I call you Adrian?’

Ten reasons why I am not attracted enough to Staff Nurse Lucy to ask her out.

1. Hairy arms – blonde hairs but far too many of them.

2. Has seen Sir Cliff Richard in Wuthering Heights, eleven times.

3. Thought Tolstoy wrote Love in a Cold Climate.

4. Lucinda.

5. Prefers normal to lemon Jif.

6. Thinks it’s exciting that Chris Evans has bought a radio station from Richard Branson for eight million pounds. She thinks they are ‘two fun guys’.

7. Likes Princess Anne because she is ‘hard-working’.

8. Failed the Auberon Waugh test.

9. Unwittingly let on that she has a neon sign in her lounge window, which flashes ‘Merry Yuletide’ every three seconds.

10. Claims never to have even heard of the Independent, let alone read it.

Sunday November 30th

Dr Fong has allowed William to go home, even though William shouted, ‘Please, Dad, please, I want to stay with Staff Nurse Lucy.’

My father was there. He said, sounding like his old self, ‘If you don’t shut your trap, lad, I’ll shut the bleeder for you.’

William shut his trap and allowed me to dress him in his outdoor clothes. He was escorted out of the hospital by his entourage, consisting of me, Rosie, my father, my mother, Ivan and Tania.

He held my hand in the car and refused to let it go. It was a bit awkward changing gear, but I didn’t mind.

Monday December 1st

Phoned bank successfully! I have got £7,961.54 in a high-interest account. I know it’s correct because a robot called Jade told me.

My mother has written a poem called, ‘A Weeping Womb’. She is sending it to the Daily Express, to a bloke called Harry Eyres. I told her that it stood no chance of being published. Harsh, I know, but I can’t bear her to be disappointed.

The Weeping Womb by Pauline Mole

Hush! Is that weeping? Listen awhile –

’Tis something within me –

Not distant (a mile)

Quiet! Is that sobbing?

From whence does it come?

My pelvis is throbbing

Quite near to my bum,

Hark to the crying!

Pay heed to the pain

My womb – it is dying!

Ne’er fertile again!

She slipped this under my door last night.

When I saw her at breakfast I made no reference to it. What could I possibly say? Ivan is behind all this: he believes that ‘Everybody has a talent, it’s just that our society cannot encompass…’ etc., etc., etc., blah, blah, blah.

> Tuesday December 2nd

Jesus Christ almighty! God save me from this biblical-like curse which has fallen on me!

A letter from Sharon Bott, with whom I once had a frenzied sexual relationship.

Dear Aidy,

This must come as a bit of a downer. I belong in the past, I know, but it weren’t me who wanted to send this letter. It is my son Glenn. He is a big lad of 12 now and he wants to know who his father is. And the thing is, Aidy, I don’t know. As you found out I was having relations with you and Barry Kent at the same time. I have written to Barry the same as you. Glenn says that you and Barry should take a DNA test to find out who is his dad. He is a good lad at home, never no trouble. I don’t know why the teachers are against him at school. I’m sorry to bother you with this only I had to do it for Glenn. Can you give me a ring? I work shifts at Parker’s Poultry, but I’m home at ten. Me and Glenn have seen you on Cable. You were quite good. Did you see that Barry has won a prize for writing a book about a blind man? It was in the Mercury last night.

Yours faithfully,

Sharon L. Bott

No way! No way! No way is she forcing me to accept Glenn ‘The Teachers Are Against Him’ Bott as my son. I’ve got one son. Another is surplus to requirements.

I showed the letter to Rosie, who said, ‘I know Glenn Bott. He’s a psycho, but he has got your nose. He helps out on a stall at Leicester market on Fridays after school. The one opposite Walker’s, the pork butcher’s.’

I phoned the Bott house. A little kid told me that ‘Mam’s gone to work.’

Wednesday December 3rd

William returned to Kidsplay today. He was greeted like a returning hero by the other children, though the teachers were distinctly cool. There have been several copy-cat incidents of children placing foreign objects in their ears (lentils, beads). Mrs Parvez is away with a stress-related illness.

Phoned Sharon late tonight. It was hard to concentrate due to the old sexual frisson and the background noise of television and yelling of children. It was an awkward conversation. I kept getting flashbacks of the two of us engaging in sexual intercourse on the pink velour sofa in my parents’ house on Thursday nights while they were out having marriage guidance.

I told Sharon that I was unlikely to be Glenn’s father due to an abnormally low sperm count, but she asked if I would take the test ‘for Glenn’. What could I say but yes? She put the phone down, saying, ‘Douggie’s just come in.’

Thursday December 4th

At four o’clock I drove to Leicester, parked in the Shires car park and walked through the Christmas shoppers to the market place. I stood outside Walker’s, the pork butcher’s, and watched the fruit stall opposite.

It didn’t come as a complete shock to find that Glenn is the same boy who’s been hanging about outside our house for the last few months. He’s tall for his age, and if he had a decent haircut and stopped glowering he’d be quite a handsome lad. He was dressed as though he lived on the streets of Hell’s Kitchen, New York, in ludicrously baggy trousers and a Puffa jacket. When he came round to the front, to tidy the fruit, I saw that he was wearing trainers the size and shape of small bulldozers.

The owner of the stall, a weasel-faced man, with earrings and a grey ponytail, seemed content to let Glenn do most of the work, apart from handling the money. I presumed this was Douggie, apparently Sharon’s live-in partner.

As I watched Glenn I tried to get in touch with my emotions. What exactly did I feel?

Diary, I felt nothing.

I could tell even from a distance that the boy didn’t have a single strand of intellectual DNA in his body.

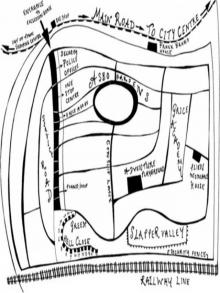

Sharon lives on the dreaded Thatcher Estate. I parked outside 19 Geoffrey Howe Road and decided to activate the car alarm and fit the steering lock on the Montego. The battered wooden gate scraped on the concrete path as I pushed it open. There was a picture of a large Devil Dog saying, ‘Go Ahead, Make My Day,’ propped against the front-room window.

Sharon opened the door before I could knock. She looked like Moby Dick with a perm. I could barely discern the Sharon I once knew from the flesh mountain she had become. The cigarette between her podgy fingers looked tiny, like the ones made of confectionery I used to ‘smoke’ as a boy.

She led me into the front room where two shaven-headed little boys were sitting on a sofa, watching a video. The TV screen showed a maniac with a hedge-trimmer pursuing a girl with large breasts down the steps of a dark cellar. The smallest boy picked up a cushion and hid his face behind it.

I was not introduced to them and, after a swift glance at me, they turned their attention back to the screen. Sharon indicated that I was to sit in one of the two matching armchairs. The carpet felt sticky beneath my feet.

She stubbed out her cigarette in a saucer. It was inconceivable to me that I had ever had carnal knowledge of this woman. A loud atonal cacophony from the television prompted me to ask Sharon if we could talk in the kitchen, though once we’d arrived there, I wished we’d stayed where we were.

‘I’ve not ‘ad time to wash up yet,’ she said, looking around at the spectacular chaos.

I looked through the grimy window into the garden. A sodden mattress lay in the long grass. Glenn’s bike was out there, padlocked to the concrete post of the washing-line. The spillage of light from the kitchen window showed that the bike was well maintained: the chrome trims and the spokes sparkled. I was pleased to see that the boy had fitted a padlock and chain to one wheel, and a cycle lock to the other.

Sharon handed me a piece of paper, which told me where and when to go for a blood test: 10.30 Monday December 8th at the clinic in Prosper Road. ‘Barry’s solicitor ’as arranged it all,’ she said. She kept glancing nervously at the narrow, gold-coloured watch which lay between the folds of fat around her wrist.

I said, ‘Has Glenn shown any preference as to who his natural father is?’

Sharon was rinsing a mug under the cold tap. ‘He’s not,’ she said. ‘But it might be better for me if it’s Barry, maintenance wise.’

‘And certainly better for me, if it’s Barry, maintenance wise,’ I said.

She offered me tea, but I declined. She told me that I would receive a copy of the results from a laboratory, and then we could ‘take it from there’.

When I got home I asked my mother if she could locate any photographs of me at the age of twelve. She sorted through a few shoeboxes and brought out a school photo. On the back was written ‘Adrian, aged eleven and a half in my father’s anal handwriting. When I turned it over I was shocked to see a picture of Glenn Bott looking up at me. My mother wanted to know why I wanted a photograph of myself at that age. I could not answer her.

Sunday December 7th

Staff Nurse Lucy rang to say that I’d left A. N. Wilson’s biography of Tolstoy in William’s bedside locker. She was passing our house; she lives in Clematis Close –should she drop it in? I said I didn’t think it would squeeze through the letterbox. ‘If Tolstoy had died at thirty-five you might have stood a chance,’ I joked. She asked how old Tolstoy was when he died. ‘In his nineties,’ I said. I waited for her to say that she was busy on the ward, but she seemed to have plenty of time to talk. She said that after work she would walk round to Wisteria Walk with Lucinda. I begged her not to. I wanted to sit and read the Observer in peace – but she insisted.

Rosie and my mother got themselves into a lather of excitement, and Ivan went upstairs and came down in a shirt and toning tie. I told them all not to waste so much nervous energy. I am not in the least attracted to Staff Nurse Lucy.

I tried to keep her and Lucinda on the doorstep, but William pulled Lucinda inside to play with his farmyard, which is stocked with dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals, so I reluctantly showed Staff Nurse Lucy into the kitchen, where I found a Sains-bury’s chocolate gâteau thawing in her honour. In the subsequent conversation it emerged that her favourite poet is Barry Kent, her favourite singer Liam Gallagher. I had to get up and leave the table. Sh

e stayed two long hours. She pronounced the gateau ‘yummy’. Just before she left, she went upstairs with me and my mother to watch William and Lucinda putting the dinosaurs to bed in the farmhouse.

‘Ah, bless,’ said Lucy. ‘They get on so well, don’t they?’

I looked at my mother’s face and saw that, in her mind’s eye, she had me and William installed in Clematis Close with Lucy and Lucinda. When they’d gone I disabused her of this idea, citing the hairy blonde wrists. My mother said, ‘A tube of Nair would sort that problem out.’

An air of heavy disappointment hangs over the house.

As I was putting him to bed William asked when Lucinda was coming to play again.

I replied, ‘Never.’

Monday December 8th

I needn’t have changed my underwear. I wasn’t asked to remove my clothes, just roll my sleeve up. I felt rather weak when I spotted the syringe and I looked away while a fat bloke in a white coat took my blood. To distract myself I muttered the words of the Lord’s Prayer. The blood-taker said, ‘Pardon?’

I opened my eyes and saw him syringing my dark red blood into a little plastic bottle. ‘I didn’t speak,’ I said.

‘You did,’ he said. ‘You said, “Amen.” Have you, too, found the Lord?’

As I was fastening my cuff, he took a leaflet from the drawer in his desk and placed it in front of me. He belongs to a sect called Godhead. They believe that the world is going to end a second after the stroke of midnight on January 1st in the year 2000. I put my coat on and stood by the door, but he wouldn’t let me go until he’d explained that the Dome at Greenwich was to be the site of ‘Satan’s Last Stand’. According to him, Mr Peter Mandelson is the Prince of Devils, and the entire Cabinet is made up of demons. He said that Jack Cunningham has cloven hoofs and has to have his shoes made bespoke. I thanked him for the information and he thanked me for listening, saying, ‘A lot of people think we’re cranks.’

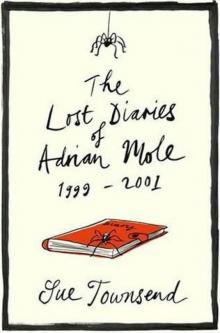

Adrian Mole 07; The Lost Diaries 1999-2001

Adrian Mole 07; The Lost Diaries 1999-2001 The Growing Pains of Adrian Mole

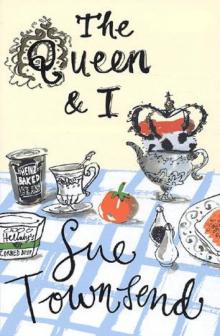

The Growing Pains of Adrian Mole The Queen and I

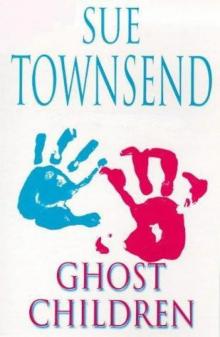

The Queen and I Ghost Children

Ghost Children Adrian Mole and the Weapons of Mass Destruction

Adrian Mole and the Weapons of Mass Destruction True Confessions of Margaret Hilda Roberts Aged 14 ¼

True Confessions of Margaret Hilda Roberts Aged 14 ¼ Adrian Mole: The Cappuccino Years

Adrian Mole: The Cappuccino Years Number 10

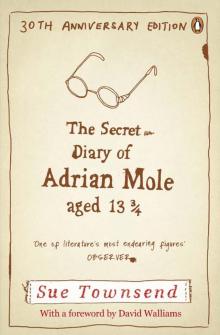

Number 10 The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3/4

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3/4 True Confessions of Adrian Albert Mole

True Confessions of Adrian Albert Mole The Woman Who Went to Bed for a Year

The Woman Who Went to Bed for a Year Adrian Mole: The Prostrate Years

Adrian Mole: The Prostrate Years Adrian Mole: The Wilderness Years

Adrian Mole: The Wilderness Years Queen Camilla

Queen Camilla The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3⁄4 am-1

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3⁄4 am-1 The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13¾ (1982)

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13¾ (1982) The True Confessions of Adrian Mole, Margaret Hilda Roberts and Susan Lilian Townsend

The True Confessions of Adrian Mole, Margaret Hilda Roberts and Susan Lilian Townsend Adrian Mole: Diary of a Provincial Man

Adrian Mole: Diary of a Provincial Man The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole Aged 13 3/4 (Adrian Mole 1)

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole Aged 13 3/4 (Adrian Mole 1)