- Home

- Sue Townsend

The Woman Who Went to Bed for a Year Page 2

The Woman Who Went to Bed for a Year Read online

Page 2

Brianne said, ‘We’re both seventeen. We took our A levels early.’

‘I would have taken mine early but I had a personal tragedy…’ Poppy paused, waiting for Brianne to ask about the nature of the tragedy. When Brianne remained silent, she said, ‘I can’t talk about it. I still managed to get four A*s. Oxbridge wanted me. I went for an interview but quite honestly I couldn’t live and study somewhere so old-fashioned.’

Brianne asked, Where was your interview — Oxford or Cambridge?’

Poppy said, ‘Do you have auditory defects? I told you, I was interviewed in Oxbridge.’

‘And you were offered a place to study at Oxbridge University?’ Brianne checked, ‘Remind me, where is Oxbridge?’

Poppy mumbled, ‘It’s in the middle of the country, ‘and went out.

Brianne and Brian Junior had been interviewed at Cambridge University, and both of them had been offered a place. The Beaver twins’ small fame had gone before them. At Trinity College they were given what looked like an impossibly difficult maths problem to solve. Brian Junior went to a separate room with an invigilator. When they each put down their pencil after fifty-five minutes of frenzied workings-out on the A4 paper supplied, the chair of the interviewing panel read their workings as if they were a chapter of a racy novel. Brianne had meticulously, if unimaginatively, worked her way straight to the solution. Brian Junior had reached it by a more mysterious path. The panel declined to ask the twins about hobbies or pastimes. It was easy to tell that they did nothing outside of their chosen field.

After the twins had turned the offer down, Brianne explained that she and her brother would follow the famous professor of mathematics Lenya Nikitanova to Leeds.

‘Ah, Leeds,’ said the chairperson. ‘It has a remarkable mathematical faculty, world class. We tried to tempt the lovely Nikitanova here by offering her disgracefully extravagant inducements, but she emailed that she preferred to teach the children of the workers — an expression I have not heard since Brezhnev was in office — and was taking up the post of lecturer at Leeds University! Typically quixotic of her!’

Now, in Sentinel Towers student residence, Brianne said, ‘I’d sooner try the dress on in private. I’m shy about my body.’

Poppy said, ‘No, I’m coming in with you. I can help you.’

Brianne felt suffocated by Poppy. She did not want to let her inside her room. She did not want her as a friend but, despite her feelings, she unlocked the door and let Poppy inside.

Brianne’s suitcase was open on the narrow bed. Poppy immediately began to unpack and put Brianne’s clothes and shoes away in the wardrobe. Brianne sat helplessly on the end of the bed, saying, ‘No, Poppy. I can do it.’ She thought that when Poppy had gone, she would arrange her clothes to her own satisfaction.

Poppy opened a jewellery box decorated in tiny pearlised shells and began to try on various pieces. She pulled out the silver bracelet with the three charms: a moon, a sun and a star.

The bracelet had been bought by Eva in late August to celebrate Brianne’s five A*s at A level. Brian Junior had already lost the cufflinks his mother had given him to commemorate his six A*s.

‘I’ll borrow this,’ Poppy said.

‘No!’ Brianne shouted. ‘Not that! It’s precious to me.’ She took it from Poppy and slipped it on to her own wrist.

Poppy said, ‘Omigod, you’re such a materialist. Chill out.’

Meanwhile, Brian Junior paced up and down in his shockingly tiny room. It took only three steps to move from the door to the window He wondered why his mother had not rung as she had promised.

He had unpacked earlier and everything had been neatly put away. His pens and pencils were lined up in colour order, starting with yellow and finishing with black. It was important to Brian Junior that a red pen came exactly at the centre of the line.

Earlier that day, once the twins’ belongings had been brought up from the car, their laptops were being charged, and the new Ikea kettles, toasters and lamps had been plugged in, Brian, Brianne and Brian Junior had sat in a line on Brianne’s bed with nothing to say to each other.

Brian had said, ‘So,’ several times.

The twins were expecting him to go on to speak, but he had relapsed into silence.

Eventually, he cleared his throat and said, ‘So, the day has come, eh? Daunting for me and Mum, and even more so for you two — standing on your own two feet, meeting new people.’

He stood up and faced them. ‘Kids, make a bit of an effort to be friendly to the other students. Brianne, introduce yourself, try to smile. They won’t be as clever as you and Brian Junior, but being clever isn’t everything.’

Brian Junior said, in a flat tone, ‘We’re here to work, Dad. If we needed “friends” we’d be on Facebook.’

Brianne took her brother’s hand and said, ‘It might be good to have a friend, Bri. Y’know, like, somebody I could talk to about…’ She hesitated.

Brian supplied, ‘Clothes and boys and hairdos.’

Brianne thought, ‘Ugh! Hairdos? No, I’d want to talk about the wonders of the world, the mysteries of the universe.’

Brian Junior said, ‘We can make friends once we ye obtained our doctorates.’

Brian laughed, ‘Loosen up, BJ. Get drunk, get laid, hand an essay in late, for once. You’re a student, steal a traffic cone!’

Brianne looked at her brother. She could no more imagine him roaring drunk with a traffic cone on his head than she could see him on that stupid programme Strictly Come Dancing, clad in lime-green Lycra, dancing the rumba.

Before Brian left, there were some badly executed hugs and backslaps. Noses were kissed instead of lips and cheeks. They trod on each other’s toes in their haste to leave the cramped room and get to the lift. Once there, they waited an interminable time for the lift to travel up six floors. They could hear it wheezing and grinding its way towards them.

When the doors opened, Brian almost ran inside. He waved goodbye to the twins and they waved back. After a few seconds, Brian stabbed at the Ground Floor button, the doors closed and the twins did a high five.

Then the lift returned with Brian its captive.

The twins were horrified to see that their father was crying. They were about to step in when the doors crushed shut, and the lift jerked and groaned itself downstairs.

‘Why is Dad crying?’ asked Brian Junior.

Brianne said, ‘I think it’s because he’s sad we’ve left home.’

Brian Junior was amazed. ‘And is that a normal response?’

‘I think so.’

‘Mum didn’t cry when we said goodbye.’

‘No, Mum thinks tears should be reserved for nothing less than tragedy.’

They had waited by the lift for a few moments to see if it would return their father again. When it did not, they went to their rooms and tried, but failed, to contact their mother.

3

At ten o’clock Brian Senior came into the bedroom and started to get undressed.

Eva closed her eyes. She heard his pyjama drawer open and close. She gave him a minute to climb into his pyjamas and then, with her back turned to him, she said, ‘Brian.’ I don’t want you to sleep in this bed tonight. Why don’t you sleep in Brian Junior’s room? It’s guaranteed to be clean, neat and unnaturally tidy.’

‘Are you feeling poorly?’ Brian asked. ‘Physically?’ he added.

‘No,’ she said, ‘I’m fine.’

Brian lectured, ‘Did you know, Eva, that in certain therapeutic communities, patients are banned from using the words, “I’m fine.”? Because invariably, they are not fine. Admit it.’ you’re distraught because the twins have left home.’

‘No, I’m glad to see the back of them.’

Brian’s voice trembled with anger. ‘That’s a very wicked thing for a mother to say.’

Eva turned over and looked at him. We made a pig’s ear of bringing them up,’ she said. ‘Brianne lets people walk all over her, and Brian Junior panics if

he has to talk to another human.’

Brian sat on the edge of the bed. ‘They’re sensitive children, I’ll give you that.’

‘Neurotic is the word,’ Eva said. ‘They spent their early years sitting inside a cardboard box for hours at a time.’

Brian said, ‘I didn’t know that! What were they doing?’

‘Just sitting there in silence,’ Eva replied. ‘Occasionally they would turn and look at each other. If I tried to take them out of the box they would bite and scratch. They wanted to be together in their own box-world.’

‘They’re gifted children.’

‘But are they happy.’ Brian? I can’t tell.’ I love them too much.’

Brian went to the door and stood there for a while, as though he were about to say something more. Eva hoped that he wouldn’t make any kind of dramatic statement. She was already worn out by the strong emotion of the day. Brian opened his mouth, then evidently changed his mind, because he went out and closed the door quietly.

Eva sat up in bed, peeled the duvet away and was shocked to see that she was still wearing her black high heels. She looked at her bedside table, which was crowded with almost identical pots and tubes of moisturising cream. ‘I only need one,’ she thought. She chose the Chanel and threw the others one by one into the waste-paper basket on the far side of the room. She was a good thrower. She had represented Leicester High School for Girls in the javelin at the County Games.

When her Classics teacher had congratulated her on setting the new school record, he had murmured, ‘You’re quite an Athena, Miss Brown-Bird. And by the way, you’re a smashing-looking girl.’

Now she needed the lavatory. She was glad that she had persuaded Brian to knock through into the box room and create an en-suite bathroom and toilet. They were the last in their street of Edwardian houses to do so.

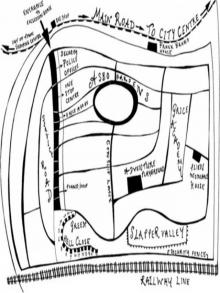

The Beavers’ house had been built in 1908. It stated so under the eaves. The Edwardian numbers were surrounded by a stone frieze of stylised ivy and sweet woodbine. There are a few house buyers who choose their next property for purely romantic reasons, and Eva was such a person. Her father had smoked Woodbine cigarettes and the green packet, decorated with wild woodbine, was a fixture of her childhood. Luckily, the house had been lived in by a modern-day Ebenezer Scrooge who had resisted the 1960s hysteria to modernise. It was intact, with spacious rooms, high ceilings, mouldings, fireplaces and solid oak doors and floors.

Brian hated it. He wanted a ‘machine for living’. He imagined himself in a sleek white kitchen waiting by the espresso machine for his morning coffee. He did not want to live a mile from the city centre. He wanted a Le Corbusier-style glass and steel box with rural views and a big sky. He had explained to the estate agent that he was an astronomer and that his telescopes would not cope with light pollution. The estate agent had looked at Brian and Eva and been mystified as to how two such extremes of personality and taste could have married in the first place.

Eventually, Eva had informed Brian that she could not live in a minimalist modular system, far away from street lighting, and that she had to live in a house. Brian had countered that he did not want to live in an old pile in which people had died, with bedbugs, fleas, rats and mice. When he first viewed the Edwardian house, he’d complained that he could feel a ‘century of dust clogging my lungs’.

Eva liked the fact that the house was opposite another road. Through the large, handsome windows she could see the tall buildings of the city centre and, beyond that, woodland and the open countryside, with hills in the far distance.

At last, due to the extreme shortage of modernist living quarters in rural Leicestershire, they had bought the detached Edwardian villa at 15 Bowling Green Road for £46,999. Brian and Eva took possession in April 1986 after three years of living with Yvonne, Brian’s mother. Eva had never regretted standing up to Brian and Yvonne about the house. It had been worth enduring the three weeks of sulking that followed.

When she turned the light on in the bathroom, she was confronted by myriad images of herself. A thin, early-middle-aged woman with cropped blonde hair, high cheekbones and French-grey eyes. At her instruction —she thought it would make the room appear larger — the builder had installed large mirrors on three sides of the room. Almost immediately she had wanted to tell him to take most of them away, but hadn’t had the courage. So, whenever she sat down on the lavatory she could see herself ad infinitum.

She removed her clothes and stepped into the shower, avoiding the mirrors.

Her mother had said to her recently, ‘No wonder you’ve got no flesh on your bones, you never sit down. You even eat your dinner standing up.’

This was true. After she had served Brian, Brian Junior and Brianne, she would go back to the stove and pick at the meat and vegetables in their respective saucepans and roasting tins. Anxiety about cooking a meal, taking it to the table on time, keeping it hot and hoping that the conversation around the table would not be too contentious, seemed to produce a surge of stomach acid that made food dull and tasteless to her.

The wire shelf unit in the corner of the shower was a jumble of shampoos, conditioners and shower gels. Eva spent a few moments selecting her favourites and threw the rejects into the bin next to the sink. Then she dressed quickly and put on her high-heeled court shoes. They gave her an extra three and a half inches in height, and she needed to feel powerful tonight. She strode around the room, rehearsing what she was going to say to Brian if he came back and tried to get into their bed.

She would have to act quickly, before she lost her nerve.

She would bring up how he undermined her in public.’ the way he introduced her to his friends by saying, ‘And this is the Klingon.’ How he had bought her twenty-five pounds’ worth of lottery tickets for her last birthday.

But then she thought about how quickly his bombast deflated, and how sad he had looked when she had asked him to sleep somewhere else. She stood near the bedroom door for a few moments, thinking through the consequences, then climbed back into bed, withdrawing from the potential battle.

She was startled awake at 3.1 5 a.m. by Brian screaming and fighting the duvet. His bedside light snapped on. When her eyes focused on her surroundings, she saw Brian stamping his foot on the carpet and holding his right calf.

‘Cramp?’ she said.

‘Not cramp! Your fucking high heels! You’ve kicked a hole in my bloody leg!’

‘You should have stayed in Brian Junior’s room and not come sneaking back into mine.’

Brian said, ‘Your room? It used to be ours.’

Brian was not good with pain or blood and here he was in the early hours of the morning, with both. He began to wail. When Eva had orientated herself.’ she could see that there actually was a hole in his leg.

‘A lot of blood … wash the wound clean,’ he said. ‘You’ll have to bathe it with distilled water and iodine.’

Eva could not leave the bed. Instead, she reached over and plucked the bottle of Chanel No. 5 off her bedside table. She pointed the nozzle at Brian’s wound and pressed, keeping her finger on the spray mechanism. Brian squealed, hopped across the beige carpet and out of the door.

She had done the right thing, Eva thought, as she drifted back off to sleep. Everybody knows that Chanel No. 5 is a good antiseptic in an emergency.

At about five thirty Eva was woken again.

Brian was limping around the bedroom.’ yelling, ‘The pain! The pain!’ at regular intervals. When Eva sat up, Brian said, ‘I phoned NHS Direct. They employ morons! Idiots! Plonkers! Fools! Halfwits! Dingbats! Cretins! Hamburger flippers! Pond life! An African witch doctor would have been better informed!’

Eva said wearily, ‘Brian, please. Don’t you get tired of fighting the world?’

‘No, I don’t much like the world.’

Eva felt a terrible pity for her husband as he stood at the end of the bed, naked, with a white linen napkin tied around one leg and with toast crumbs in his beard. Eva turned away from him.

/> He was an intrusion in what was now her bedroom.

Brianne wondered how long Poppy would be crying. She could hear her sobbing through the party wall.

She looked at the alarm clock she had owned since she was a child. Barbie was pointing to the four and Ken was indicating the one. It wasn’t what she had expected from her first night at university.

She thought, ‘I’ve been dragged into the pages of an EastEnders script by that awful girl.’

At about half past five she was startled awake from a ragged sleep by somebody banging on her door. She could hear Poppy whimpering She froze. There was no escape from her on the sixth floor of the accommodation block — and anyway, the window only opened a few inches.

‘It’s me — Poppy. Let me in?’

Brianne shouted, ‘No! Go to sleep, Poppy!’

Poppy beseeched, ‘Brianne, help me! I’ve been attacked by a man with one eye!’

Brianne opened her door and Poppy fell into the room. ‘I’ve been attacked!’

Brianne took a look up and down the corridor. It was empty. The door to Poppy’s room was open and the emo track that she played incessantly — A Fine Frenzy’s ‘Almost Lover’ — was blaring out. She glanced into Poppy’s room. There was no sign of a violent struggle. The bedcover was unwrinkled.

When she returned to her own room, she was disconcerted to find that Poppy was wearing her favourite fluffy acrylic dressing gown, had climbed under her duvet and was sobbing into her pillow Brianne didn’t know what to do, so she put the kettle on and asked, ‘Shall I phone the police?’

‘Don’t you think I’ve been defiled enough?’ shouted Poppy. ‘I’ll just sleep in your bed tonight, with you.’

Thirty minutes later, Brianne was clinging on to the edge of the bed. She vowed to go to the university library tomorrow and source a book on how to grow a backbone.

4

On the second day Eva woke and threw the duvet back and sat on the side of the bed.

Then she remembered that she didn’t have to get up and make breakfast for anyone, yell at anyone else to get up, empty the dishwasher or fill the washing machine, iron a pile of laundry, drag a vacuum cleaner up the stairs or sort cupboards and drawers.’ clean the oven or wipe various surfaces, including the necks of the brown and the red sauce bottles, polish the wooden furniture, clean the windows or mop the floors, straighten rugs and cushions, shove a brush down various shitty toilets or pick up soiled clothing and place it in a laundry basket, replace light bulbs and toilet rolls, pick up things from downstairs that were upstairs and bring them down or pick up things from upstairs that were downstairs, fetch dry-cleaning, weed the borders, visit garden centres to buy bulbs and annuals, polish shoes or take them to the key cutter, return library books, sort recycling, pay paper bills, visit one mother and worry about not visiting one mother-in-law, feed the fish and clean out the filter, answer the phone for two teenagers and pass on messages, shave legs or pluck eyebrows, give self-manicure, change the sheets and pillow cases on three beds (if it was Saturday), hand wash woollen jumpers and dry flat on a bath towel, pay bills, shop for food she wouldn’t eat herself, wheel it to the car, unload it into the boot, drive home, put the food away in the fridge and the cupboards and, on tiptoe, place tins and dried goods on a shelf that exceeded her reach but was perfectly comfortable for Brian.

Adrian Mole 07; The Lost Diaries 1999-2001

Adrian Mole 07; The Lost Diaries 1999-2001 The Growing Pains of Adrian Mole

The Growing Pains of Adrian Mole The Queen and I

The Queen and I Ghost Children

Ghost Children Adrian Mole and the Weapons of Mass Destruction

Adrian Mole and the Weapons of Mass Destruction True Confessions of Margaret Hilda Roberts Aged 14 ¼

True Confessions of Margaret Hilda Roberts Aged 14 ¼ Adrian Mole: The Cappuccino Years

Adrian Mole: The Cappuccino Years Number 10

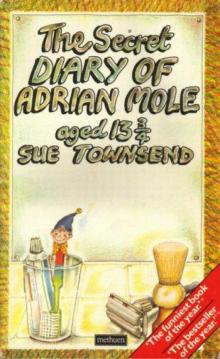

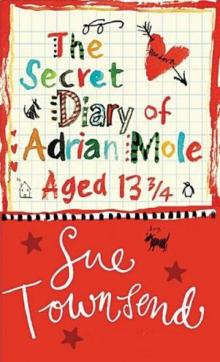

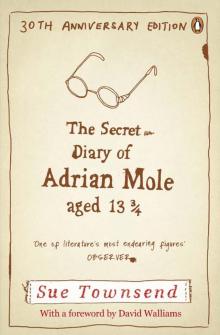

Number 10 The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3/4

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3/4 True Confessions of Adrian Albert Mole

True Confessions of Adrian Albert Mole The Woman Who Went to Bed for a Year

The Woman Who Went to Bed for a Year Adrian Mole: The Prostrate Years

Adrian Mole: The Prostrate Years Adrian Mole: The Wilderness Years

Adrian Mole: The Wilderness Years Queen Camilla

Queen Camilla The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3⁄4 am-1

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3⁄4 am-1 The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13¾ (1982)

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13¾ (1982) The True Confessions of Adrian Mole, Margaret Hilda Roberts and Susan Lilian Townsend

The True Confessions of Adrian Mole, Margaret Hilda Roberts and Susan Lilian Townsend Adrian Mole: Diary of a Provincial Man

Adrian Mole: Diary of a Provincial Man The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole Aged 13 3/4 (Adrian Mole 1)

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole Aged 13 3/4 (Adrian Mole 1)