- Home

- Sue Townsend

Adrian Mole: The Cappuccino Years Page 25

Adrian Mole: The Cappuccino Years Read online

Page 25

I said, ‘The cheque was for a million pounds, Mr Patience. What did you think it was? His pocket money?’

Patience said, ‘He was waving it around in the playground. Some of the first-years were sick with excitement.’

I threatened to take Glenn away from the school.

Patience said, ‘You won’t get him into another school round here. Bott is known to staff rooms up and down the county. He is infamous.’

Glenn was sitting on a scratched-up wooden bench outside the office. He stood up as I came out and said, ‘Sorry, Dad.’

Saturday March 28th

William and Glenn asked me what we were going to ‘do’ over the weekend. I said that when I was a boy I didn’t do anything. I just hung about the house until it was time to go back to bed.

Monday March 30th

My mother rang and asked me what I would like for my birthday on Thursday. I said, ‘I would like a lilac lavatory brush and holder from the Innovations catalogue.’

She said, ‘Don’t be ridiculous!’

I said, ‘I’m perfectly serious. Archie’s brush has lost all of its bristles.’

She said, ‘I’ll get you a book token as usual.’

She asked how William was. I said, ‘He’s extremely well,’ then pointedly, ‘as is my other son, Glenn.’

She said, ‘I’m trying very hard with Glenn, Adrian, but I have to admit that…’ There was silence, then she burst out with, ‘I can’t bear the way he breathes through his mouth, and I can’t stand to watch him with a knife and fork.’

I said that I couldn’t bear the way that Ivan’s eyebrows met in the middle, or the way he knotted his tie or the way he pushed himself up against her when she was at the sink. But I replaced the receiver with a heavy heart. We had both gone too far. Dishonesty is obviously the best policy.

Tuesday March 31st

A panic attack at 3.17 a.m. What had I done with my life?

I am an unsuccessful husband.

I am a disappointing son.

I am a failed writer.

I have failed to master the Psion Organizer.

I prayed fervently that I wouldn’t fail with my sons.

Wednesday April 1st

April Fools’ Day

Oh, joy! Oh, precious rapture! A letter has arrived from the BBC!

Dear Adrian Mole,

I will cut to the chase. I have just finished reading The White Van (never mind how it got into my hand, suffice it to say that it has a large cult following here at the BBC). I am bowled over by this magnificent piece of work, and I would like to make a TV series out of it. I envisage 20 hour-long episodes.

The casting, of course, is crucial, but early thoughts include Robbie Coltrane, Dawn French, Pauline Quirke, Richard Griffiths.

I am away today on a Stress Awareness Course (mobile phones are banned). I will be back in my office tomorrow. Please telephone me then.

Yours sincerely,

John Birt

Director General

Then, handwritten,

PS. I can’t tell you how excited I am by this.

I immediately telephoned Brick Eagleburger and left a message on his voicemail asking him to ring me back. Then, after supplying the boys with food and clean clothes and conducting the now almost obligatory search for shoes, I drove round to my mother’s and photocopied the letter.

I have faxed copies to George ‘n’ Tania, Brick Eagleburger, Pandora, Barry Kent, Peter Savage and the Leicester Mercury. I then posted copies to the faxless: Nigel, Grandma and Grandad Sugden, Auntie Susan and her wife.

Dear Diary, I will sleep well tonight. John Birt has given me a wonderful thirty-first birthday present.

Thursday April 2nd

I was woken by William throwing himself on to my bed and poking the sharp corner of a birthday card into my neck. He had made the card at nursery school under the supervision of Mrs Parvez. There was a crude approximation of me on the front: a stick man with huge teeth and wild hair. Seven fingers on each hand, and wearing high-heeled shoes. Inside, Mrs Parvez had made William copy ‘To Daddy, best wishes from William’. ‘Best wishes!’ It speaks volumes about Mrs Parvez’s relationship with her own father.

Glenn hung about in the bedroom doorway, glowering and smiling in turn. His hair has grown considerably, but he still looks like a thug. I will be glad when he has outgrown his thug clothes and I can introduce him to the Next range of junior menswear.

Eventually he came forward and thrust a shop-bought card into my hand. I took it out of its lurid red envelope. The illustration on the front was of a pipe-smoking, jutting-jawed fly fisherman who was up to his waders in a river. Jut-jaw’s vintage car was parked on the bank. The boot of the car was open, showing that Jut-jaw had already caught five large fish, and placed them in a wicker basket. There was a black Labrador gazing up at its master. On the front of the card it said, ‘To A Special Father On Your Birthday’. Inside there was a verse printed in Gothic script:

Father, it’s your Special Day,

Time for fun and pleasures gay.

The sporting life it is for you, tramping through the morning

Dew, with dog and rod and fishing-line,

then home to bathe and sup and dine.

It could hardly have been more inappropriate. I loathe the great outdoors, and the thought of encouraging a harmless fish to impale itself on a sharp hook fills me with horror. However, when I saw that the boy had written ‘Love from Glenn’ in not too bad handwriting, and had scrawled thirty-one kisses on a blank interior page, I was touched.

Glenn also handed me a snake ashtray he’d made in Pottery at school. It consisted of a long thin coil of baked clay, ending in a snake’s face. He said, ‘In case you wantto start smokin’, Dad.’ The post brought cards from Pandora (Happy Birthday, Constituent), Nigel (a card that said, ‘Come out of the closet, you know you’re gay,’ with a drawing of a man stuck in a wardrobe), the Sugdens (a jut-jaw washing a sports car).

When I was in the shower somebody came round and pushed the Mole family’s cards through the front door. My mother’s card was tactless in the extreme: a cartoon balding man (who looked uncommonly like me, actually) had a bubble coming out of his mouth saying, ‘I’m over thirty, can you direct me to the Hill?’ My father’s card was of a village green cricketing scene, and several black Labradors were watching the match from various vantage-points. A woman was coming down the pavilion steps with a tray of sandwiches. The women spectators were wearing pretty frocks, hats and high-heeled shoes. My father had written: ‘Those were the days! Happy Birthday, Adrian, from Dad and Tania.’

I rang John Birt but his secretary said he was in a meeting. I was surprised to find that she didn’t know about The White Van! I rang at various intervals throughout the day, but Mr Birt seemed to go from meeting to meeting. There was a small birthday celebration at my mother’s at 4 p.m.: a Spice Girls cake and a Marks & Spencer’s party-food pack, which my mother hadn’t properly defrosted. A toast was drunk to me in sparkling wine. Rosie gave me a boot-fair find, a leatherbound copy of Chekhov’s short stories. She said, ‘It smells f------ mouldy, but it might clean up.’

I thanked her from the bottom of my heart. She is obviously the only member of my family who understands me. My mother started whimpering when Glenn levered a mini-pizza into his mouth with the flat of his knife, so I took him and William home.

At 11 p.m. an extraordinary thing: there was a knock on the door. I laid aside my copy of Lee Salk’s What Every Child Would Like His Parents to Know and went downstairs. On the doorstep was a box. I took it inside and opened the lid. A balloon floated out and hovered near the ceiling. A card inside the box said, ‘I burn for you, I yearn for you.’ Who can this be from, dear Diary?

Friday April 3rd

6.30 p.m. John Birt is now out of the office, again, on a ‘Visions and Values’ course. His secretary was unable to give me an account of his movements. I rang Brick, but he had heard nothing either. I asked to s

peak to Boston. Brick said, ‘She don’t work here no longer, Aidy. She kinda flipped and I had to let her go. She’s back on the East Coast.’

Ms Eleanor Flood arrived at her usual hour; she admired the balloon and said, ‘I didn’t know it was your birthday.’

I was quite relieved.

Tuesday April 7th

Apparently the sales figures for Offally Good! – The Book! are disappointingly low. The publishers are talking about remaindering some and pulping others. Apparently W. H. Smith have got a machine somewhere that turns books into fertilizer. My father, the book-phobic, would no doubt enjoy seeing this literature-crushing machine in operation.

Pie Crust rang and asked me to go on the Late Night with Derek and June show on Thursday. Dev Singh had to cancel due to stress. He has booked into the Priory for a week. Derek and June is filmed at studios in Soho at midnight. I said I would require a hotel room, as I was reluctant to drive both up and down the M1 on the same night due to the danger of falling asleep at the wheel.

Rosie is going to babysit.

Nothing from the BBC. A bloke called Richard Brookes, from the Observer, rang me and asked for details about the BBC deal. He told me that he had first read the treatment for The White Van three weeks ago. When I asked him how he had got his hands on it, he said that it had been passed around in the Groucho Club. I don’t know whether to be flattered or outraged.

I prayed throughout my interview that nobody of my acquaintance would watch Late Night with Derek and June tonight. First I had to go along with the lie that I was sitting at their own kitchen table, whereas in fact we were in a crappy little ‘studio’ in the red-light district. Then, to my astonishment, Derek said to me, live on camera, ‘We’ve been friends for years, haven’t we, Adrian?’

He appeared to be doing an impression of Mr Bean. He took a copy of Offally Good! – The Book!, turned to the recipe for chicken giblets in parsnip coulis, and began to read aloud.

June’s fat shoulders shook throughout. The whole interview was risibly amateurish. Derek and June made personal remarks about my appearance, then appeared to ignore me and chatted between themselves about their caravan holiday at Ingoldmells. The studio crew seemed to find their every banal utterance hysterically funny. When they turned their attention back to me it became obvious to me that Derek and June were having fun at my expense. They were, in fact, totally uninterested in offal. I felt angry and humiliated. I left the studio as soon as the filming was finished.

A spotty girl in denim shorts and thigh boots was leaning against my car smoking a cigarette. ‘Hand job?’ she said.

‘No, it’s fully automatic,’ I replied, got in and drove to the Temple Hotel in Haven Hill Gardens, W2.

Temple Hotel

2 a. m. This place is a minimalist nightmare of Japanese design. My room is white and cream, and is decorated with old Japanese petrol cans. I can’t find a way to open the wardrobes, or discover how to flush the lavatory. I will have to sleep with the lights on as don’t know how to switch them off. When I finally managed to turn the shower on it was so powerful that it hurled me out of the cubicle, then flooded the floor and gushed into the sleeping pit, where it was soaked up by the futon.

I should have paid more attention when the hall porter showed me around the room but, to be honest, I was too intimidated by his severe black uniform and French accent to concentrate.

8 a.m. I found it hard to sleep for worrying about the flood from the shower. Would they charge me for water damage to the futon? Then there were the contents of the lavatory bowl: how would I dispose of them? I made another search for the flushing mechanism, but failed to find anything remotely like a handle, a knob, a switch or a floor pump. I took a tumbler and used it to pour water into the lavatory. It took twenty minutes before the contents finally disappeared.

Saturday April 11th

Glenn told me that it’s his birthday next Saturday. ‘I’m becomin’ a teenager, Dad.’ He is very excited. I didn’t like to tell him that my own teenage years were utterly desolate and miserable. However, he has one advantage over me: he can in no way be described as an intellectual. Glenn does not lie awake pondering on the nature of existence. He lies awake wondering who Hoddle will field in the World Cup.

Monday April 13th

A postcard from Cape Cod, America! I know no one in those parts! Blank, apart from my address on one side, and on the other ‘April Fool, Nebbish!’

A mystery.

Tuesday April 14th

The shame of it! No wonder John Birt failed to ring me back. I have studied the handwritten PS endlessly, but don’t recognize the prankster’s handwriting. How will I ever overcome my terrible humiliation and disappointment?

Glenn tried to console me with a joke. ‘At least you know it weren’t me, Dad, on April 1st. I didn’t have no handwritin’.’

Wednesday April 15th

Tonight, with Eleanor’s assistance, Glenn copied out his name and address and also ‘Gazza’, ‘Hoddle’ and ‘World Cup’.

I opened a bottle of Mateus Rosé and asked Eleanor to join me in celebrating his progress. I almost wished I hadn’t – after half a glass she began to gaze at me very intensely. I think I am going off her a little.

Thursday April 16th

Eleanor rang at 7.30 a.m. (a touch early, I felt) to apologize for her melancholic behaviour. Apparently she is in therapy due to ‘inadequate nurturing and a subsequent lack of self-esteem’. I didn’t ask for details. I said that I, too, had been in therapy due to my parents’ neglect of me when young.

In thirty-one years I can remember only two acts of parental self-sacrifice from my father. The first was when I was six years old, and dropped my raspberry ripple on the sand at Wells-next-the-Sea. He gave me his own (slightly eaten). The second was when I was suspended from school for contravening the rules by wearing red socks. He took time off work and went to see the headmaster, the fearsome Mr Scruton, and forced him to make a grovelling apology.

2 a.m. Regarding the Red Socks Row. I’ve just remembered the true facts.

1. My father did not take time off from work. He was unemployed at the time.

2. He did not confront Scruton at the school. He telephoned him.

3. Scruton did not make a grovelling apology.

4. On the third day I capitulated and wore black socks to school.

Saturday April 18th

Glenn’s birthday

Glenn came into my bedroom this morning and thanked me for the ‘You’re α teenager, Son!’ card. (Picture: a blond boy with a baseball cap on back to front, sitting in front of a computer.) He asked me to read the verse inside. After I’d done so I wished I’d read the inscription thoroughly in the shop. I would almost certainly have bought another card.

‘It’s a boy!’ the midwife said. Emotions went from A to Z.

All your life I’ve guided you, taken you to school and zoo,

Helped you with your ABC, been there when you needed me.

Now you are an in-between, not child, not man, but new-turned teen.

As you make your way through life, there may be days of woe and strife

Remember I am always here to give, advise and lend an ear.

I’m your dad and you’re my son. When most is said, and all is done.

I thought Glenn was moved by these sentiments, though it’s hard to tell, with his face being as it is. He liked the England strip I bought him from JJB Sports, and went to the bathroom straight away to change into it. He’s got my legs: he doesn’t look good in shorts. William gave him a card he’d made at nursery: a cardboard football decorated in glued and painted polenta. When we were sitting eating breakfast (I insist we sit around the table for all meals – I grew up watching my mother eat standing up with her back to the sink and my father sitting on top of the pedal bin), Glenn said, ‘Am I havin’ a surprise party, Dad?’

I said, ‘No.’

Glenn said, ‘But you’d have to be sayin’ that, wouldn’t you, Dad?’

>

When he’d gone outside to kick his football up and down the yard with William, I phoned Sharon and asked her to come to a party with her children.

She sounded pleased – she’s never been to Rampart Terrace before. I then rang round my family and begged them to attend at 5 p.m., and to bring cards and presents.

I left a message on Eleanor’s machine.

I spent most of the day shopping for the ‘surprise’ party. I bought a Jane Asher football cake and thirteen candles. At 4.45 p.m. I made a huge cauldron full of mashed potatoes and put thirty-five links of Walker’s sausages into the oven. I cut up two pounds of Spanish onions and fried them slowly. I then spent the next quarter of an hour on the doorstep, looking anxiously up and down the street, praying that the guests would turn up.

Eventually, Sharon, Caister, Kent and Bradford arrived on foot, then my own family. I asked them all to wait outside until I’d lured Glenn into the yard by telling him I wanted him to help me hone my footballing skills – an unlikely story, but he fell for it. After five minutes of tedious footballing pretence I led him into the living room, which was now crowded with his friends and relations. He blushed to the roots of his hair and fell silent as the assembled company sang ‘Happy Birthday To You’.

Eleanor’s voice soared above the others; she was like a song-thrush fallen amongst crows. Tania Braithwaite said, in a loud whisper to my father as tea was served, ‘Sausages, mashed potatoes and fried onions? How very basic.’ My mother overheard and said to her, ‘What have you got against sausages?’

Adrian Mole 07; The Lost Diaries 1999-2001

Adrian Mole 07; The Lost Diaries 1999-2001 The Growing Pains of Adrian Mole

The Growing Pains of Adrian Mole The Queen and I

The Queen and I Ghost Children

Ghost Children Adrian Mole and the Weapons of Mass Destruction

Adrian Mole and the Weapons of Mass Destruction True Confessions of Margaret Hilda Roberts Aged 14 ¼

True Confessions of Margaret Hilda Roberts Aged 14 ¼ Adrian Mole: The Cappuccino Years

Adrian Mole: The Cappuccino Years Number 10

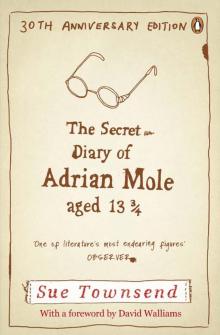

Number 10 The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3/4

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3/4 True Confessions of Adrian Albert Mole

True Confessions of Adrian Albert Mole The Woman Who Went to Bed for a Year

The Woman Who Went to Bed for a Year Adrian Mole: The Prostrate Years

Adrian Mole: The Prostrate Years Adrian Mole: The Wilderness Years

Adrian Mole: The Wilderness Years Queen Camilla

Queen Camilla The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3⁄4 am-1

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3⁄4 am-1 The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13¾ (1982)

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13¾ (1982) The True Confessions of Adrian Mole, Margaret Hilda Roberts and Susan Lilian Townsend

The True Confessions of Adrian Mole, Margaret Hilda Roberts and Susan Lilian Townsend Adrian Mole: Diary of a Provincial Man

Adrian Mole: Diary of a Provincial Man The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole Aged 13 3/4 (Adrian Mole 1)

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole Aged 13 3/4 (Adrian Mole 1)