- Home

- Sue Townsend

Adrian Mole 07; The Lost Diaries 1999-2001 Page 6

Adrian Mole 07; The Lost Diaries 1999-2001 Read online

Page 6

Peter Pig lifted his porcine head from the trough and looked up at the mercilessly grey East-Midlands sky. A cloud, which looked like a Boots cotton-wool ball, scudded across the aforementioned sky like a Eurostar train leaving Waterloo station.

Peter sighed and walked around the sty. The filth and mud oozed between his trotters. It was disgusting, the condition he had to live in, he thought. Why should farmer Hogg and his wife, Pamela, enjoy the comfort of carpets and vinyl tiles under foot while he and his fellow pigs be condemned to wading through their own excrement.

Peter looked over the sty, towards the patio where farmer Hogg and Pamela were holding a barbecue for their friends. The foul stench caused by pork fat dripping on Do It All charcoal briquettes drifted over to him, causing his eyes to run. He listened to the conversations of the humans as they gorged on their buffet, which Pamela had been preparing since the Archers finished on the radio.

Peter watched the guests quaffing Bucks Fizz and longed to feel the liquid in his own mouth. He looked across the sty to where his fellow pigs, Antonia and Miles, were having a heated discussion about the nature of existence. Peter sighed, he was sick of philosophical debate. It was just his luck to be trapped in a sty with two intellectuals. How he craved for small talk! He twitched his ears towards the patio. He strained to hear the conversation.

‘Well, I’m sick of it,’ said a grey-haired man called Ken, ‘after all Mo’s been through.’ A well-presented woman called Barbara hissed: ‘Not here, Ken, there’s a chap called Derek from the Ashby Gazette standing by the gherkin jar’. ‘I won’t be silenced,’ Ken thundered. ‘It’s unmanly of Tony to stab her in the back.’ From the sty, Peter watched as Derek turned from the pickle jar, took out his reporter’s notebook and edged towards Ken and Barbara.

It was at this point that William started whining about wanting a Noddy story. However, I continued with Sty! for a few more lines.

Another group of people provided the small talk that Peter thirsted for. From a woman in white jeans, he heard: ‘We do support the comprehensive system, but our children are terribly sensitive, so.’ And a man wearing wire Raybans opined: ‘House prices have got to come down soon. We bought ours for…’ Peter was in heaven. Later that night, the barbecue long extinguished, Peter looked up at the stars and ruminated on the nature of small talk. To help him sleep, he practised the art. He selected one of his favourite topics: ‘Call this a summer? I can’t remember the last time the sun shone.’

Within minutes, William was asleep.

Sunday, July 2

I loathe Noddy, but I had promised William, so I made up the following story.

It was Big Ears’ birthday, so, to celebrate, Noddy drove his car to Toytown. The pals went from pub to pub, drinking pints of beer. Big Ears’ face got very red and the bell on Noddy’s hat rang like mad. When they came out of the last pub, a gang of Skittles accused Big Ears of being a pervert, and started a fight. Mr Plod was called and saw Noddy head-butting the largest Skittle.

‘Hi ham takin’ you to the nearest cash point,’ said Mr Plod. ‘Tell me your PIN number Noddy.’ But, sadly, Noddy was too drunk to remember, so Mr Plod hit him hard on the head with his truncheon instead.

Good night.

Wednesday, July 5

12 Arthur Askey Way

My father originally went into hospital with fractures of the leg and various other injuries, caused when he fell off a ladder while constructing a Japanese-style pagoda for his new wife, Tania, who is obsessed with all things Oriental.

He’s been in hospital for months, suffering from a hospital-borne infection, and is now completely institutionalised. When he hears the food trolley arrive at the end of the ward at 7am, 12 noon and 5pm, his mouth fills with saliva. He claims to be happy there, says he has no worries: other people pay the bills, walk the dangerous streets, get immobilised in traffic jams, and do the Sainsbury’s run.

Sharon Bott, the mother of my son, Glenn, works as a cleaner at the hospital. She says that, as part of an infection-control programme, her mop was taken away for laboratory tests. She said that when the mop was returned to her, ‘It looked as if it had been through the mill.’

Thursday, July 6

I have just found a sheaf of poems hidden inside the panel surrounding the washbasin. They are in Glenn’s handwriting. Why he feels the need to hide the evidence of a fine sensibility is a mystery to me. This house is devoted to the creative spirit. William, for instance, has a passion for making miniature gardens in old shoe-boxes. Perhaps he will grow up to be a landscape gardener like Capability Brown or Charlie Dimmock.

My favourite poem is entitled Why?

Why?

Why, oh why do nice things die?

A leaf, a flower, a humble fly?

I will have to correct Glenn on an inaccuracy in this poem. Flies are not nice. They have vile personal habits. My second-favourite poem is called Patsy:

Patsy

I love the way your mouth goes up

When you drink from out a cup.

That Liam was no good for you

Come to me, I will be true.

I cannot give you mega-wealth

But I am young, I have my health.

Flee from London, leave your cage

But know one thing, I’m under-age

I can’t have sexual intercourse,

I’m chaste like that Inspector Morse.

When Glenn came home from school, I tackled him about the poem. He hung his head and blushed scarlet. ‘Don’t tell no one, Dad,’ he said.

Saturday July 8

My mother has called a family conference. I am the subject. My father was on the end of his hospital telephone. Others present were: Ivan Braithwaite, Tania, Mrs Wormington, and my auntie Susan, a prison warder. They are concerned that I am wasting my life. I pointed out that I am a full-time carer of two boys and a 90-year-old woman. My mother said, ‘What was the point of reading all those books if all you’re going to do with that knowledge is to wash and iron and cook. You might as well have been born a woman.’

Auntie Susan stubbed out her cigar and raked her fingers through her number two before saying, ‘Adrian, I could get you a job in the prison library.’

To shut them all up, I promised to think about it but the thought of being in contact with even literate prisoners fills me with horror. Tania said that, in her opinion, I had an unhealthy fixation with old people. ‘Why can’t you be content to do voluntary work in a retirement home? Why do you feel the need to have one living with you in your home?’ I was unable to give her an answer. When they had gone, Mrs Wormington asked, ‘Who was that stuck-up bitch in the kimono?’

Monday, July 10

Next week, I go to Wind-on-the-Wolds prison to be shown around the library. There is a part-time job available, worse luck!

Thursday, July 13

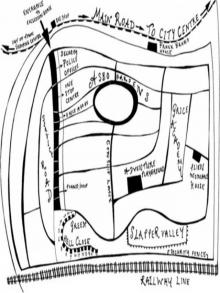

Ashby-de-la-Zouch, Leicestershire

My Mother has just phoned in a panic, gabbling about CJD. She was once driven through the village of Queniborough on the way to a garden centre in Quorn and is now convinced that she is to be the next victim in the cluster of unfortunates to have contracted the deadly disease. She has become a hypochondriac since Ivan Braithwaite moved into our house with his mania for sterilising the chopping boards and sprinkling Dettol on the new dog’s bedding.

I tried to calm her fears but she was near to hysteria and begged me to forgive her. ‘For what,’ I enquired, wondering which of her parental crimes I should forgive her for. ‘The cheap beefburgers I used to serve up, three times a week,’ she said. ‘I didn’t know they were made of bits of old spinal chord and sawdust, Aidy.’

I reassured her that the beefburgers of my childhood were so utterly disgusting that I used to surreptitiously feed the dog with them. It would take its place under the table whenever it saw my mother drag a box of the vile things out of the freezer. Personally, I’m waiting for the boil-in-the-bag cod-in-butter-sauce food scare. I must have consumed a shoal of the fish. Then there’s the frozen

beef TV dinners for one, which we used to consume on Sundays. That tinfoil couldn’t have done us much good, either. ‘It’s 100% organic food for me from now on,’ said my mother.

‘But you don’t know what to do with real food,’ I reminded her. She replied, ‘I’ve got Delia and Nigel and Jamie to help me,’ as though her ill-equipped kitchen was full of celebrity chefs jostling for space.

Friday, July 14

Mrs Wormington has gone to Mablethorpe with the Ludlows. They have got an eight-berth caravan in a field near to the sea. They asked if they could take William with them but I had to say no. He is an impressionable lad and easily picks up on the Ludlows’ verbal infelicities. Yesterday he came back from playing at their house, and when I told him it was time for bed, he said, in a Louisiana accent while showing me his left palm. ‘Tell it to the hand, cos the face ain’t listening. Leave a message after the bleep’ Peggy Ludlow said that the Jerry Springer Show had been on while William had been playing on the rug with Vince Ludlow’s socket set.

Saturday, July 15

I watched the Inside Downing Street documentary tonight. What a fine figure of a man he is. He is masterful, charming, clever and has a good head of hair. He is altogether impressive. Mr Blair, on the other hand, seemed lacklustre by comparison. He has been transformed since Leo insisted on sharing the marital bed and Euan started hitting the bottle. In fact, Tony has undergone a feminisation: his hair has turned fluffy, his voice has softened, his expression is girly, his hands move as gracefully as a geisha’s. Is he on a course of hormones that will eventually transmogrify him into Toni – the first woman Labour Prime Minister? The country should be warned. We will need time to adjust to the change.

William Hague, on the other hand, is awash with testosterone lately. He’ll be starting a parliamentary chapter of the Hell’s Angels next if he doesn’t watch his hormone levels. Does Ffion welcome this new thrusting Mussolini-like man in her bed, or is she already sleeping in the spare room, like Prince Edward’s wife?

Sunday, July 16

The Ludlows have returned home with hypothermia after walking along the promenade at Mablethorpe. Mrs Wormington has been taken to hospital in Skegness. She has been wrapped in a silver space blanket.

When Auntie Susan rang my mobile and asked angrily why I’d not turned up at the prison library as promised, I replied truthfully that I was anticipating a tragic bereavement.

Wednesday, July 19

Ashby-de-la-Zouch

The summer weather in Mablethorpe has killed Mrs Wormington. She was a perfectly fit, 90-year-old when she left my house in Ashby-de-la-Zouch on Friday, July 14, at 1.15pm. I am being specific about details because Eunice, Mrs Wormington’s daughter- in-law, has just left this house after calling to collect the dead one’s belongings. She accused me of sending ‘an ailing woman to the east coast, to die’.

It was only after she had driven off in her Reliant Robin that I realised that she was virtually accusing me of murder. I immediately called my mother, who is an acknowledged expert on litigation (she haunts the small-claims court). She advised me to seek the advice of her solicitor, Charlie Dovecote. It cost me £50, plus VAT, to be told by Dovecote that allowing a nonagenarian to ride a donkey in a stiff east wind may have been foolhardy, but did not constitute murder.

I found a bundle of old letters under Mrs Wormington’s mattress when I stripped her bed. I was glad that the horrible Eunice had missed them.

October 21, 1917

Dear Sergeant Palmer,

I hope you are now settled into your new quarters in Ypres and that the weather is pleasant. We hear most marvellous reports of General Haig’s leadership from the newspapers. I am glad that you are in such safe hands. Thank you for asking me to call you Cedric. However, I feel it is far too early in our friendship for such intimacy. We have only known each other for a year.

Yours with best wishes,

Miss Broadway

This, I presume, was Mrs Wormington’s maiden name. Social intercourse was conducted with such delicacy in those days. It’s no wonder that Mrs Wormington was shocked at Denise Van Outen’s grubby little TV show. Even I, an admirer of the female breast, begin to tire of prime-time mammaries.

Thursday, July 20

William wanted to know where Mrs Wormington had gone. I said she had gone on a long journey to a place where she would be in peace. I went on a bit, about Mrs Wormington running up hills and picking wild flowers under the warming rays of the sun, etc. Perhaps I went too far down the pastoral path, because when William was watching Glenn clean his roller-blade boots I heard him say, ‘Mrs Wormington’s not dead, Glenn. She’s gone to live in Teletubby Land.’

Friday, July 21

A car in which Jack Straw was being conveyed was stopped by police for speeding at 103mph. I hope the full might of the law is brought to bear on the miscreant. I am still smarting from the tirade of abuse I received from a traffic policeman because I drove at 32mph in Foxglove Avenue, a 30mph zone. When I remarked, humorously, ‘I’m not exactly Jeremy Clarkson’, the policeman sneered, ‘No, he’s taller, got more hair, and is almost certainly richer and more famous than you are, sir’ I thought of reporting him to the Police Complaints Board, but wasn’t sure if sarcasm counted as assault – though I still feel hurt by it.

Saturday, July 22

I went to see Pandora at the MP’s surgery today. I wanted to talk to her about my theory that Mr Blair has secretly embarked on a course of hormones that will transform him from Tony to Toni. I reminded her that he’d recently stated that he disliked wearing a suit.

‘Don’t be so bloody ridiculous,’ she snapped. ‘Get out and give your seat to a constituent with a genuine problem’ I pointed out that there was nobody else waiting to see her. ‘Apathetic bastards,’ she raged of the electorate. ‘I could have stayed in London and picked up my bowling bag from Prada.’

I had no idea she’d taken up such a middle-aged, boring sport.

Monday, July 24

Ashby-de-la-Zouch

There was a surprisingly large turn-out for Mrs Wormington’s funeral this morning. I hadn’t known she was a member of so many societies and clubs. There were mourners representing Amnesty International, the Fox And Ferret ladies’ darts team and the Cacti Club of Great Britain. I hadn’t realised she had such Catholic tastes.

In the time she lodged with me, most of our conversations had been about biscuits, though towards the end of her life she spoke obsessively about the state of the Queen Mother’s teeth. William begged to be allowed to go to the funeral; I gave my permission, but warned him against talking in the church. The boy has a voice like a town crier. He let me down only once, when he asked, in the lull between a hymn and a prayer, ‘Dad, why do old people smell?’ The church was packed with the elderly, who failed to see the charm or humour in the boy’s innocent question.

One old bloke along the pew shouted to his deaf neighbour, ‘He wants a bloody good hiding’ I had warned William what to expect: that there would be a box called a coffin and that Mrs Wormington would be inside it, dead. He seemed to take in this fact, but when the coffin started to be lowered into the grave, William shouted, ‘You’d better get out now, Mrs Wormington’ He said later, at home, that he’d thought dead people came back to life, like Kenny in South Park. At the service, I read a poem I’d written. It seemed to go down quite well – though my mother said afterwards at the funeral lunch that she thought it was gross self-indulgence on my part and should never have been torn from my pad of A4.

Requiem for Mrs Wormington

She was not a little old lady

She was six foot tall.

She didn’t smile sweetly

She wouldn’t play ball.

She didn’t wear chiffon

Or white gloves to wave.

She lived through two wars

But wasn’t called brave.

She drew her own curtains

And cooked her own dinners

She worked in

a factory with good folk and sinners.

Her overdraft didn’t exceed £1.50.

But she didn’t get praised for being so thrifty.

Farewell Mrs Worthington, fan of Nye Bevan

I hope you are warm again up there in Heaven.

Several people asked me the significance of ‘warm again’, not knowing that Mrs Wormington had died of hypothermia after holidaying in Mablethorpe.

Tuesday, July 25

Glenn and William are on holiday from school for six weeks. What am I going to do with them? I have no funds with which to entertain them. We are only one day into the break, but William has already declared himself to be ‘bored’. I told him that, when I was a lad, I entertained myself with non-stop activities. But, in truth, all I can remember doing is staring out of the window and waiting for school to begin again.

Wednesday, July 26

I reluctantly drew out £50 from the building society, bought a family rail ticket and took my sons to Tate Modern. No one warned me about the vast metal spider in the Turbine Hall. William is an arachnophobe and froze with fear on seeing it. He then emitted a piercing scream. An American tourist asked me if William was an ‘auditory accompaniment to Louis Bourgeois’s sculpture’. I said ‘no’, that he was just a little boy who was scared of spiders.

Thursday, July 27

Concorde is off the front pages; no British people were killed.

Saturday, July 29

Ashby-de-la-Zouch

Ivan Braithwaite continues to be fascinated by what he calls ‘working-class culture’. He has suggested that our family go to Skegness on what he calls a ‘bucket-and-spade holiday’. He drivelled on about candyfloss, donkeys and ‘the glorious vulgarity of the amusement arcade’.

I had no choice but to say yes. I can’t afford my preferred holiday – visiting literary shrines throughout the world. In fact, so far I have only visited one: Julian Barnes’s house in Leicester. Though he left there when he was six weeks old.

Adrian Mole 07; The Lost Diaries 1999-2001

Adrian Mole 07; The Lost Diaries 1999-2001 The Growing Pains of Adrian Mole

The Growing Pains of Adrian Mole The Queen and I

The Queen and I Ghost Children

Ghost Children Adrian Mole and the Weapons of Mass Destruction

Adrian Mole and the Weapons of Mass Destruction True Confessions of Margaret Hilda Roberts Aged 14 ¼

True Confessions of Margaret Hilda Roberts Aged 14 ¼ Adrian Mole: The Cappuccino Years

Adrian Mole: The Cappuccino Years Number 10

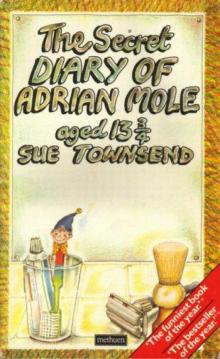

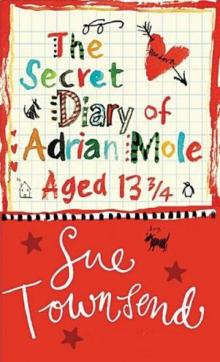

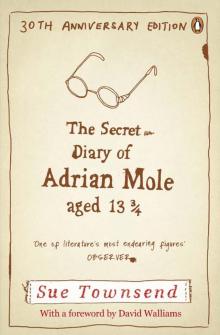

Number 10 The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3/4

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3/4 True Confessions of Adrian Albert Mole

True Confessions of Adrian Albert Mole The Woman Who Went to Bed for a Year

The Woman Who Went to Bed for a Year Adrian Mole: The Prostrate Years

Adrian Mole: The Prostrate Years Adrian Mole: The Wilderness Years

Adrian Mole: The Wilderness Years Queen Camilla

Queen Camilla The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3⁄4 am-1

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3⁄4 am-1 The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13¾ (1982)

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13¾ (1982) The True Confessions of Adrian Mole, Margaret Hilda Roberts and Susan Lilian Townsend

The True Confessions of Adrian Mole, Margaret Hilda Roberts and Susan Lilian Townsend Adrian Mole: Diary of a Provincial Man

Adrian Mole: Diary of a Provincial Man The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole Aged 13 3/4 (Adrian Mole 1)

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole Aged 13 3/4 (Adrian Mole 1)