- Home

- Sue Townsend

Queen Camilla Page 9

Queen Camilla Read online

Page 9

Beverley bridled and said, ‘I’ve only ever had one client whose hair fell out.’

In her youth Beverley had been briefly apprenticed to a unisex salon in the town. She was still at the shampooing and sweeping-up stage when she had been dismissed for ‘gross insubordination’ after her malicious gossip caused two clients, the wife and the mistress of a third client, to fight among the washbasins in the salon. The subsequent car chase had escalated into tragedy: an attempted murder charge, a hospital admission and a botched suicide.

Camilla had been reluctant to entrust her hair to Beverley, but she couldn’t bring herself to go to Grice’s salon, Pauper’s, again. Not after the last time, when a sixteen-year-old boy stylist had minced up and told her that her hairstyle, the one she had kept for over thirty years, made her look like ‘one of them old women what models thermal underwear on the back pages of pensioner magazines’.

Camilla was always careful what she said in front of Beverley, who had a gift for wheedling things out of one. Only yesterday Beverley had caused trouble on the estate by claiming she had seen Mr Anwar, the highly prudish owner of the ‘Everything A Pound’ shop, sneaking into the entrance of Grice-A-Go-Go, the pole-dancing club in the shopping parade. The gentleman in question had not been Mr Anwar, but a similar-looking, morbidly obese, middle-aged Hindu, an environmental health inspector, making a professional visit. Mrs Anwar had still not returned from her brother’s house, where she had fled to avoid the scandal.

Beverley had once auditioned to work in Grice-A-Go-Go, but Arthur Grice had laughed at her performance on the pole and told her to come back when she had lost four stone. Beverley had gone home and told Vince she’d got the job but couldn’t take it because she’d been allergic to the pole. ‘I forgot, I can only wear precious metal,’ she had lied.

Beverley stuffed Camilla’s dripping hair into a plastic shower cap and said, ‘Maddo Clarke told me he saw Princess Michael taking her Louis Vuitton luggage down from her attic.’

‘How would Maddo know?’ asked Camilla, who was certain that Maddo Clarke had never set foot inside Princess Michael’s house.

‘He’s a peeping Tom,’ said Beverley, matter-of-factly.

Camilla said, ‘What’s the significance of the luggage?’

Beverley said, ‘She’s planning to go back to London, after the election.’

Camilla said, ‘The New Cons don’t stand a chance of being elected.’

‘I dunno,’ said Beverley, looking at the television where Boy English was shown in flattering profile being interviewed on Politics F’da Yoot.

‘I wun’t climb over ’im to make a cup of cocoa,’ said Beverley.

Camilla said, ‘He’s terribly nice. I knew his mother, in the old days.’

Beverley said, ‘Do you miss your old life, Camilla?’

Camilla said, ‘Oh, I ache for it sometimes. But what else could I do? I was terribly in love with Charles.’

Beverley sighed and said, ‘An’ you gave it all up for love, like me. I’d have been a famous actress by now if I hadn’t bumped into Vince’s dodgem car an’ broke ’is nose.’

Beverley locked the door and drew the kitchen curtains against the snooping cameras, and they lit cigarettes.

Camilla said, ‘I hope Boy doesn’t get elected, Bev. I couldn’t bear to be the wife of the King of England.’

Beverley’s eyes widened, she pounced on to this titbit like a tiger leaping on to a soft-eyed antelope and said, ‘Charlie can’t be the King until the Queen is dead.’ She gasped. ‘Don’t tell me the Queen is dying! Oh, my God! What’s she got? A bad heart? Cancer? TB? How long’s she got to live?’

Camilla’s scalp felt as though it was on fire. She said, ‘Bev, I’m terribly sorry, but there’s something dreadfully wrong with my scalp.’

Beverley pulled up the shower cap and inspected Camilla’s scalp. ‘Fuckin’ ’ell,’ she said. ‘Get your head under that cold tap, quick.’

When Camilla’s hair had been towelled dry and the fire in her scalp had almost subsided, they watched the remainder of the Boy English interview.

As a concession to the young viewing audience Boy had left off his tie and was wearing jeans and an open-necked pink shirt. Together with his stylist he had agonized about trainers. Should he buy some, and if so, which brand? He had tried a few pairs on in the privacy of his office, but he decided that he looked ridiculous in them, and anyway, they made him feel as though he had bloody mattresses for feet. He much preferred to feel the hard ground when he walked.

The interviewer was a black girl called Nadine, who spoke in a form of ‘Yoof’ speak he could barely understand. He got through by doing a lot of quick summations but really, he thought, this is worse than doing bloody Beowulf at Oxford. He had just finished talking about his passion for Bob Marley and Puff Daddy when Nadine hit him below the belt by saying in very clear English indeed, ‘Boy, do you still have a serious cigarette habit?’

Boy had a split second in which to think. If he admitted he was a smoker, he was jeopardizing his chances of winning the next election. If he said he was a non-smoker, he might be exposed as a liar. Perhaps somebody had evidence; but he didn’t know how. He only ever smoked in his own house these days, when his wife was out, with the blinds drawn and an extractor fan going. In the recent past he had visited Gasper’s, one of the private smoking clubs that had sprung up in Soho, but he could no longer take the risk, not now his face was so well known.

Boy put on his ‘I’m going to make a brave statement now’ expression and said, ‘Nadine, I’m going to be absolutely straight with you. In my youth I experimented with cigarettes, most people did. I was anxious to fit in with my peers.’ He ducked his head and gave a shy smile, ‘I was not a confident youngster, I thought that cigarettes would make me look cool. I got drawn into it when I was seventeen, in my last year at school.’

Beverley, watching at home, said, ‘What took him so long? I were on twenty a day by the time I was fourteen.’

In the studio, Boy was saying, ‘I bought an expensive lighter. Soon there were ashtrays in every room, then, before I knew it, I was up to ten a day.’

Beverley snarled, ‘Amateur.’

Boy lowered his eyes. His lashes, enhanced by a touch of midnight-black Maybelline, fluttered against his pale skin. This single gesture won him hundreds of thousands of votes from a particular demographic: women, ex-smokers.

‘What about the Exclusion Zones, will you keep them?’

Boy said carefully, ‘We are currently reviewing the situation. Exclusion Zones have undoubtedly had a part to play in making the streets safer for hard-working, taxpaying families.’

Nadine said, ‘OK. Now I’m gonna ask you to do our quick quiz. Which jeans, Levi’s or Wrangler?’

Boy answered, ‘Levi’s.’

Nadine asked, ‘Who’s your favourite slapper, Jordan or Jodie?’

Boy hesitated; he didn’t want to antagonize either slapper’s supporters.

‘Pass,’ he laughed.

Nadine’s next question was easier to answer, ‘Queen Elizabeth or Queen Camilla?’

‘Oh, I think Queen Camilla,’ he said, without hesitation.

Camilla could not help feeling pleased, though the thought of actually being the Queen of England horrified her.

Vince Threadgold almost fell through the kitchen door. King followed him in.

‘You’ve bin drinkin’,’ accused Beverley.

‘It’s our lad’s birthday,’ slurred Vince.

‘I know that,’ said Beverley savagely.

‘King’s birthday?’ asked Camilla, stretching her hand out to stroke the old Alsatian. ‘How old is he?’

There was an uncharacteristic silence from the Threadgolds, as both waited for the other to speak. Eventually Vince said, ‘We ’ad a lad, Aaron. He were born thirty years ago.’

‘’E was took off us by social services,’ said Beverley, lighting another cigarette even though the first was still smouldering in the ash

tray.

‘’E kept breakin’ ’is bones,’ said Vince.

‘An’ they thought me an’ Vince was doin’ it,’ said Beverley.

‘I knew I weren’t,’ said Vince, ‘so I thought Bev must ’ave been.’

‘An’ I knew I weren’t,’ said Beverley, ‘so…’

‘So how did he break his bones?’ asked Camilla.

‘’E ’ad brittle bone disease,’ said Beverley with a ghastly smile, ‘but by the time social services found out, ’e’d bin adopted, an ’e didn’t know us.’

Beverley’s face crumpled, ‘An’ now ’e won’t want to know us, will ’e? Not living in an Exclusion Zone.’

Vince patted Beverley’s shoulder.

Camilla said, ‘Children always want to know their blood parents, Bev. He’ll come looking for you, one day.’ She left as soon as decency allowed.

By six o’clock in the evening, a story had spread around the estate that the Queen had six months/two weeks/days to live, because she was suffering from heart disease/leukaemia/tuberculosis. It took only a few hours for the rumour about the Queen’s imminent death to reach Prince Charles; Maddo Clarke told him at the frozen-food cabinet in Grice’s Food-Is-U.

‘Sorry to ’ear ’bout your mam,’ said Maddo. ‘I only seen her today, an’ I thought she looked a bit green round the gills.’

Charles took a step back from Maddo’s beery breath and said, ‘Yes, she’s been in dreadful pain, but she’ll be perfectly all right soon.’

‘Yeah,’ said Maddo, ‘it’ll be a merciful release.’

Charles frowned and thought, Mummy’s toothache can’t be pleasant but it hardly warrants the tears in Maddo’s eyes.

‘It must be ’ard for you,’ said Maddo. ‘Seeing as ’ow close you are to your mam.’

‘Well, I’ll certainly be glad when it’s all over,’ said Charles, as he searched fruitlessly through the cabinet for a frozen organic chicken.

‘Can’t bear to see ’er suffer, eh?’ Maddo put a tattooed hand on Charles’s shoulder.

Charles gave up looking for an organic chicken, and the cooking instructions on the battery chickens appeared to be written in Chinese anyway. He moved on down the aisle to the greengrocery section.

Maddo followed him, saying, ‘I never got over my mam’s passin’. When she took bad they ’ad to get the fire service to lift her out of the bedroom.’

‘Whatever for?’ asked Charles.

‘She were quite a big lady,’ said Maddo. ‘She were forty-two stone at the end.’

‘How appalling,’ said Charles.

‘It weren’t ’er fault!’ said Maddo angrily. ‘Nobody can ’elp their glands, can they?’

‘Indeed not,’ said Charles. ‘I meant, how appalling for you.’

‘I worshipped that woman,’ Maddo said, openly crying. ‘When we buried her, a pizza box blew into the grave. It were a sign from Mam that she were all right.’

Charles put his wire basket down and his arms around Maddo, who was now distraught and attracting attention from the other shoppers.

‘She loved her pizza. She’d get through three a night,’ Maddo sobbed. He recited like a litany his mother’s favourites. ‘Hawaiian, five cheeses, and pepperoni with extra onions. Every night, regular as clockwork, at nine o’clock, the pizza van would arrive. I’ve been drunk ever since.’ He was mopping his eyes now, with Charles’s handkerchief. ‘So look after your mam, and if there’s owt I can do to make sure your mam’s last few days or weeks are ’appy, then let me know.’

Charles was baffled. It was hard for him to take in. Why hadn’t his mother told him she was terminally ill? He’d believed her when she’d told him that she was suffering from toothache. Outside the shop, with the money allocated for groceries still in his pocket, he bumped into his brother, Andrew, who was arm-in-arm with a thin red-haired woman in city shorts and high heels.

Before Charles could get a word in about their mother, Andrew said, ‘Charlie, this is Marcia Boycott, or as The News of the Screws called her, Marcia Boy Cock.’ He nudged Charles and laughed, ‘D’you geddit?’

‘So unfair,’ said Marcia, assuming that Charles was aware of her notoriety. ‘The boy was gagging for it.’ She pushed her red mane back with a slim white hand. ‘He lied his fifteen-year-old head off in court. I got no credit for getting him through his French GCSE.’

‘Marcia’s just moved into Pedo Street,’ said Andrew.

‘You make it sound as though I had a choice,’ said Marcia bitterly. She turned her intense gaze on to Charles and, addressing him directly, asked, ‘Do you think it’s fair that I’ve lost my job, that I’m on a list of known paedophiles, that I’m barred from going anywhere near a school or playground? I’ve been demonized for teaching a clumsy provincial schoolboy the art of love.’

Charles stammered, ‘It does seem a little harsh.’ He was longing to get away but Marcia continued.

‘None of the other boys I slept with complained.’

‘Quite,’ said Charles.

Andrew said, ‘The sneaky little bastard went to the police when Marcia refused to cough up for an iPod.’

‘I have my principles,’ said Marcia. ‘I will not pay for sex.’

Charles judged that this was not the moment to tell his brother that their mother was terminally ill. He could see that Andrew was eager to get Marcia somewhere he could give her a good seeing-to. As Charles hurried home to share the news with Camilla, he comforted himself with the thought that at least he wouldn’t have to be king. He thanked God that he now lived in a republic and the monarchy would never be restored. The New Cons would never win an election; Boy English had too many skeletons in his cupboard, and Charles was sure that one day they would come out dancing.

Mr Anwar told Violet Toby that the Queen was dying when Violet was in his shop looking for a butter dish. ‘It is most sad, she is a very gracious lady, only last week she was in the shop buying clothes pegs.’

Violet had been forced to sit down; she had lived next to the Queen for the past thirteen years and she’d taught her how to cook and clean and look after herself.

‘When I first met her,’ said Violet, ‘she couldn’t mash a spud, and didn’t know you ’ad to shake a bottle of HP to get the sauce to come out.’

Anwar said, ‘She will be a great loss to our community. Most of the people here are the dregs of society.’ He looked out of the shop window to where two struck-off solicitors were arguing over a can of Kestrel lager.

‘I ’ope you’re not callin’ me a dreg,’ said Violet. ‘I’m only ’ere because of our Barry. If it weren’t for ’im I could live anywhere I pleased.’

Mr Anwar said, ‘I am also punished for my son’s behaviour. He rang the police and told them that Osama bin Laden was living in our attic. The boy was thirteen, he’d been reading The Diary of Anne Frank, he’d fallen under the book’s influence. It was foolish, yes, but why punish the whole family?’

‘Didn’t they find some guns in the attic, though?’ asked Violet.

‘A few Kalashnikovs,’ said Mr Anwar. ‘Souvenirs from Afghanistan.’

‘Never mind,’ said Violet, comfortingly. ‘You’d ’ave been put in ’ere anyway, because of your weight, wouldn’t you? What are you now, thirty stone?’

When Violet got home, she dumped her shopping on the kitchen table and went straight round to the Queen’s house. She was disappointed to find that the lights were out and the front door was locked. She would have to wait until the morning before hearing the clinical details of the Queen’s terminal illness.

Charles had also called at his mother’s house and, finding her out, had knocked on Violet’s door. Violet had obviously been crying, thought Charles. Mascara had run down her cheeks, leaving dark trails as if a spider had gone for a jog after falling into black paint.

‘I ’eard about your mam,’ said Violet. ‘I don’t know what I’ll do without her.’

‘I can’t understand why Mummy didn’t tell me,’ said Charles.

‘She wun’t want to worry you,’ said Violet, who wished that Barry would stop telling her about the alarming thoughts that went through his head. ‘Do your brothers and sister know?’ she asked.

‘Not yet,’ said Charles. He was dreading breaking the news to them.

Before Charles had the chance to speak to his siblings, the Queen rang him.

‘Charles,’ she said, ‘I’ve something terribly important to tell the family.’

‘Oh, Mummy, I can’t bear it,’ said Charles.

Both of them were conscious that all telephone conversations were listened to by the security police. It made them more circumspect than usual.

The Queen said, ‘Can you and Camilla come to Anne’s at eight tonight?’

‘Of course,’ said Charles. ‘But are you well enough?’

The Queen said, ‘The pain has been dreadful, but it’s out now.’

‘Yes,’ said Charles. ‘Maddo Clarke told me. I do wish you’d told me yourself, Mummy.’

The Queen said, ‘I can’t be bothering you with every detail of my life.’

Charles thought, or death. He said, ‘You are magnificently brave, Mummy. When my turn comes I hope I shall be able to display such courage.’

The Queen said, ‘The worst bit is the waiting.’

Charles said, ‘I can imagine. It must be agony.’

‘But there’s television to watch, and magazines,’ said the Queen.

After he replaced the receiver, Charles thought, I doubt if there are televisions or magazines in Heaven, but if his mother was comforted by that belief, then who was he to disabuse her? When Charles thought about Heaven, he imagined it to be an English pastoral landscape with farmers in moleskin trousers driving horse-drawn ploughs, but he couldn’t quite decide where he fitted into this heavenly Utopia. Would there be a roped-off enclosure for VIPs or would the dead have equal rights?

15

The Queen had asked for the meeting to take place in the Princess Royal’s house because it was the largest private venue available. Anne’s husband, Spiggy, had knocked their living room, hall and kitchen into one large space. He’d demolished the walls one night after returning home from a karaoke night at the One-Stop Centre, where he’d bought a lump hammer from a glue sniffer desperate for a couple of quid.

Adrian Mole 07; The Lost Diaries 1999-2001

Adrian Mole 07; The Lost Diaries 1999-2001 The Growing Pains of Adrian Mole

The Growing Pains of Adrian Mole The Queen and I

The Queen and I Ghost Children

Ghost Children Adrian Mole and the Weapons of Mass Destruction

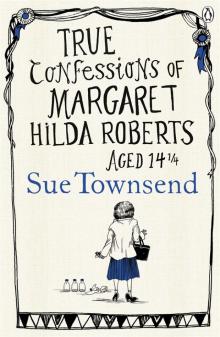

Adrian Mole and the Weapons of Mass Destruction True Confessions of Margaret Hilda Roberts Aged 14 ¼

True Confessions of Margaret Hilda Roberts Aged 14 ¼ Adrian Mole: The Cappuccino Years

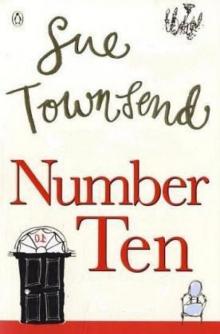

Adrian Mole: The Cappuccino Years Number 10

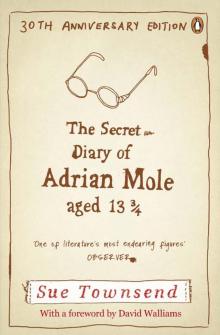

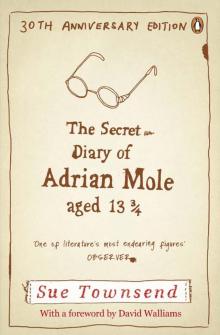

Number 10 The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3/4

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3/4 True Confessions of Adrian Albert Mole

True Confessions of Adrian Albert Mole The Woman Who Went to Bed for a Year

The Woman Who Went to Bed for a Year Adrian Mole: The Prostrate Years

Adrian Mole: The Prostrate Years Adrian Mole: The Wilderness Years

Adrian Mole: The Wilderness Years Queen Camilla

Queen Camilla The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3⁄4 am-1

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3⁄4 am-1 The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13¾ (1982)

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13¾ (1982) The True Confessions of Adrian Mole, Margaret Hilda Roberts and Susan Lilian Townsend

The True Confessions of Adrian Mole, Margaret Hilda Roberts and Susan Lilian Townsend Adrian Mole: Diary of a Provincial Man

Adrian Mole: Diary of a Provincial Man The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole Aged 13 3/4 (Adrian Mole 1)

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole Aged 13 3/4 (Adrian Mole 1)